SAVING GILI T

From the effects of unrestrained tourism

13 December 2015

**With special thanks to the Lee Foundation for supporting our research.

Direct flights to anywhere are symbolic of convenience and progress. But for the person in search of something more – whether out of pure interest or simply for bragging rights – transits and transfers are a must.

How else would they gloat about the exoticism of their travels?

The Gili Islands off Lombok are one such destination that requires some transiting and transferring. When one finally lands on those sandy beaches, one can pretend to be a semi-hardened traveller deserving of several beers and behaving badly.

As we stepped off the fast boat from Bali, putting our feet into the clear waters of Gili Trawangan, or Gili T for short, we were immediately struck by what we saw. There was a certain familiarity. Sun-kissed bodies in tank tops and micro-shorts; young (and mainly Caucasian) men and women speaking and laughing loudly, beer in one hand, Sampoerna cigarette in the other; and tanned leathery locals shouting, “Taxi? Taxi?” It was as though someone had carved out a chunk of Bali’s Kuta and transplanted it onto Gili T.

Gili T is the largest of the three Gili islands off Lombok; the other two being Gili Meno and Gili Air.

During the high season, Gili T, which is approximately three kilometres long and two kilometres wide, welcomes up to five thousand tourists every day. No less staggering is the two thousand tourists that flock to the island daily in the low season. We spent a week there in the low season, but can be forgiven for believing otherwise because we narrowly avoided accidents on the road with other cyclists and the cidomo or horse-cart taxis.

But, we weren’t there to sip on cocktails or to plait our hair. We were there to see the uglier side of Gili T.

FIVE THOUSAND TOURISTS?! THAT'S A LOT OF RUBBISH!

Gili T doesn’t produce or manufacture anything apart from perhaps seafood, coconuts and drunk tourists. The island’s supply of drinking water, primarily for visitors, is bought and transported from Lombok, in plastic bottles big and small. It was only in 2011 that Berkat Air Laut started its desalination operations, selling treated water to certain hotels, restaurants and private residences. Even so, businesses such as Aston Sunset Beach continue to buy their drinking water.

In addition, Aston has in-house water treatment equipment that further treats the desalinated water for use in cooking and washing. They also treat waste water that is used on their grounds.

“The desalinated water is may be OK for cooking and washing, but we don’t serve as drinking water to our guests,” says Emanuel Prasodjo, Aston’s general manager.

That would explain the very salty water that we showered with at our hotel, Coconut Garden. And my green tea was so salty that I had just the one cup the entire week. Having said that, I can’t be sure if we were washing with and drinking desalinated water, untreated well-water or even plain seawater.

Whilst 10-litre water dispenser containers can be cleaned and reused, the standard 330ml or 1l bottles are discarded as trash, whether in the sea, by the roadside or on the island’s main rubbish dump site. Plastic drinking water bottles aside, the average holidaymaker’s daily waste includes human waste, toilet paper, food bits, plastic wrappers for this, that and the other, empty suntan lotion bottles, laundry detergent packets, Bintang beer bottles, plastic lighters and anything else that you can think of. Multiply that by five thousand, add the islanders’ own waste, and that’s a whole lot of rubbish.

Moreover, the construction of new resorts and villas is relentless and all along the many unpaved roads on the island lie piles of construction material and furnishings – cracked toilet bowls, broken floor tiles, plastic pipes.

Jalan Kelapa, a key arterial road that leads from the island’s main drag straight into the centre of the island, seemed to be a popular dumping ground. In between higher-end and ostensibly more exclusive villas lay piles of rubbish on either side of the long road, some still smoking from fires lit the night before.

From our own experiences in other developing parts of Southeast Asia, it’s safe to say that the locals are as much to blame as foreigners and tourists for litter and waste pollution. I remember a boat trip on the Nam Ou in Laos from Nong Khiau north to Muong Noi when a young woman nonchalantly flicked her food wrapper out to the side of the boat, letting the wind and current take it away.

It’s gone, it’s disappeared, it’s dealt with.

On the northern tip of Gili T is Oceano Resort Jambuluwuk. It is garish in theme and décor. The first thing people see is the giant bow of a ship in a front garden made to look like a zoo with plastic animal sculptures. Zebras, elephants and monkeys never looked so odd.

But, it wasn’t the front bits of Oceano that we were interested in. Riding on our bicycles, we took a side road off the main tourist trail and found ourselves on a dirt track used by locals. We knew this because as we taking photographs of Oceano’s de facto dump site just behind their walls, a workman from the resort next door called out, “Tourist road up there. Why you come here? Why you taking photo?”

It seemed to us as if Oceano literally dumped their rubbish over their garden wall. Either that or they and everyone else around them used the back roads as a rubbish dump.

It reminded me of my time in China where people swept the dirt and litter from their house or restaurant onto the road and left it there.

It’s gone, it’s disappeared, it’s dealt with.

This is a video of the surroundings outside the villa walls of Oceano. It highlights the wanton disposal of rubbish behind the resort:

REDUCE, REUSE AND RECYCLING EFFORTS

“If people and the government don’t start doing their part, this island is going to sink in garbage and there won’t be any Gili to speak of in five may be 10 years,” says Bryce Adamson, owner of Gili T Resorts.

“Nobody’s going to want to come to an island full of garbage,” Adamson adds.

Delphine Robbe, project manager and co-ordinator at Gili Eco Trust (GET), knows this all too well. Since around 2009, Robbe, who has lived on the island since 2003, has been working the ground with local and foreign businesses encouraging them to sort their rubbish, reduce waste and to start composting where possible. Rubbish that has been sorted is sent to Lombok where it’s sorted again and either recycled or upcycled, incinerated or dumped into a landfill that is already full.

“The islanders are now more co-operative because they know that they can make money out of collecting and sorting trash. But, they [and others] were resistant at the beginning because they thought I was using the NGO money for my own business. But, now they know that this is not the case,” Robbe explains.

GET is an NGO that was started in 2000 to protect the Gilis’ coral reefs from destructive fishing practices. Its work now extends to other eco-conservation projects and animal welfare. GET works with several NGOs including Front Masyarakat Peduli Lingkungan (FMPL) on the rubbish project.

Adamson adds, “What GET is doing is very important. If all the 600 plus businesses pitched in to do their bit and to pay the monthly trash collection fee, we could really clean up this island!” According to Adamson, the island administration charges businesses 500,000 rupiah (approximately SGD50/USD35) a month for rubbish collection. But, it would seem that not everyone pays this fee. And yet, the rubbish is collected without question.

“The rubbish is collected anyway because people can make money from selling the rubbish to GET. So, the businesses aren’t motivated to pay the monthly fee. But it’s only 500,000 rupiah. It isn’t a big deal. Sadly, so many of the business owners here are just out to make the most money they can in the shortest possible time. If they sense a problem, they’ll sell their business and move on,” Adamson laments.

Adamson, who is married to a woman from Lombok, owns his property, which is his vested interest in the island. This is why he supports Robbe’s efforts and has offered her the use of his barge should she need to transport large quantities of rubbish or other items to Lombok and/or Bali. Because there is no sewage system on the island, Adamson uses a septic tank on his premises, which is emptied regularly and the contents sent to Lombok for treatment and disposal.

“But so many owners I know just dig a hole and dump everything in there because they don’t want to incur the expense. A lot of the island’s well-water is already contaminated. And there’s nothing that anyone can do about it because there’s no real government here - no paperwork, no certifications, no safety standards. There’s an island head, but you don’t see him. Many of the decisions are made by a ‘mafia’ and corruption is a very serious problem.”

Photo: Robbe's tenacity has encouraged islanders to sort their rubbish. Many of them earn a small income from doing so.

ONE GIANT PILE OF STINKING RUBBISH

Speaking of the village head, we had the good fortune of meeting him. Pak Haji Lukman was on site at the Bangketan rubbish dump, not a kilometer from our hotel. He was there to say a few words for a video that Robbe was filming as part of her campaign efforts. We’ve provided a link to her campaign at the end of this story.

There had been no rain on the island for about eight months. It was about noon when we visited the dumpsite. The stench of rubbish rotting in the tropical heat bore through my nostrils and the sight of it made my stomach churn. Cows rummaged through the trash foraging for food scraps. Scrawny horses struggled up the slight incline with their loads. Children in the ramshackle huts just by the dump ran barefoot in the dirt with not a care in the world.

Robbe squints in the glare of the sun beating down on her uncovered head.

“We need to flatten this dump and rejuvenate the land and we need the government, businesses on this island and tourists to do their part.

“It’s a four-step plan. Drive more recycling and sorting; encourage composting; start over by clearing and flattening this dump; and initiate Green Police to enforce rules and regulations.”

Also in the video is Febriarti Khairunnisa, co-founder of Bank Sampah Bintang Sejahtera, an environmental social enterprise based in Lombok. Febriarti met Robbe earlier in the year at the International Women’s Conference (IWC 2015) that was held in Bali in April. Robbe, with her impressive command of Bahasa Indonesia, has made great strides in her negotiations with local government and businesses. But, I reckon that Febriarti represents a local connection for GET.

Elaborating on the challenges they face, “The problem stems from the government’s short-term project-based ‘solutions’. They provide machines and leave it to the communities to manage. No needs assessment, no education, no training. Two crusher machines were given to Gili Trawangan several years ago, but they were never used and now cannot be used at all.”

She adds, “The government plans to install an incinerator here in 2016. This is sure to kill tourism.”

Febriarti estimates that the incinerator would cost about 5.4 million rupiah; money that would be much better spent on funding a waste management plan.

NO MOTORISED VEHICLES, PLEASE; CIDOMO OR BICYCLE ONLY

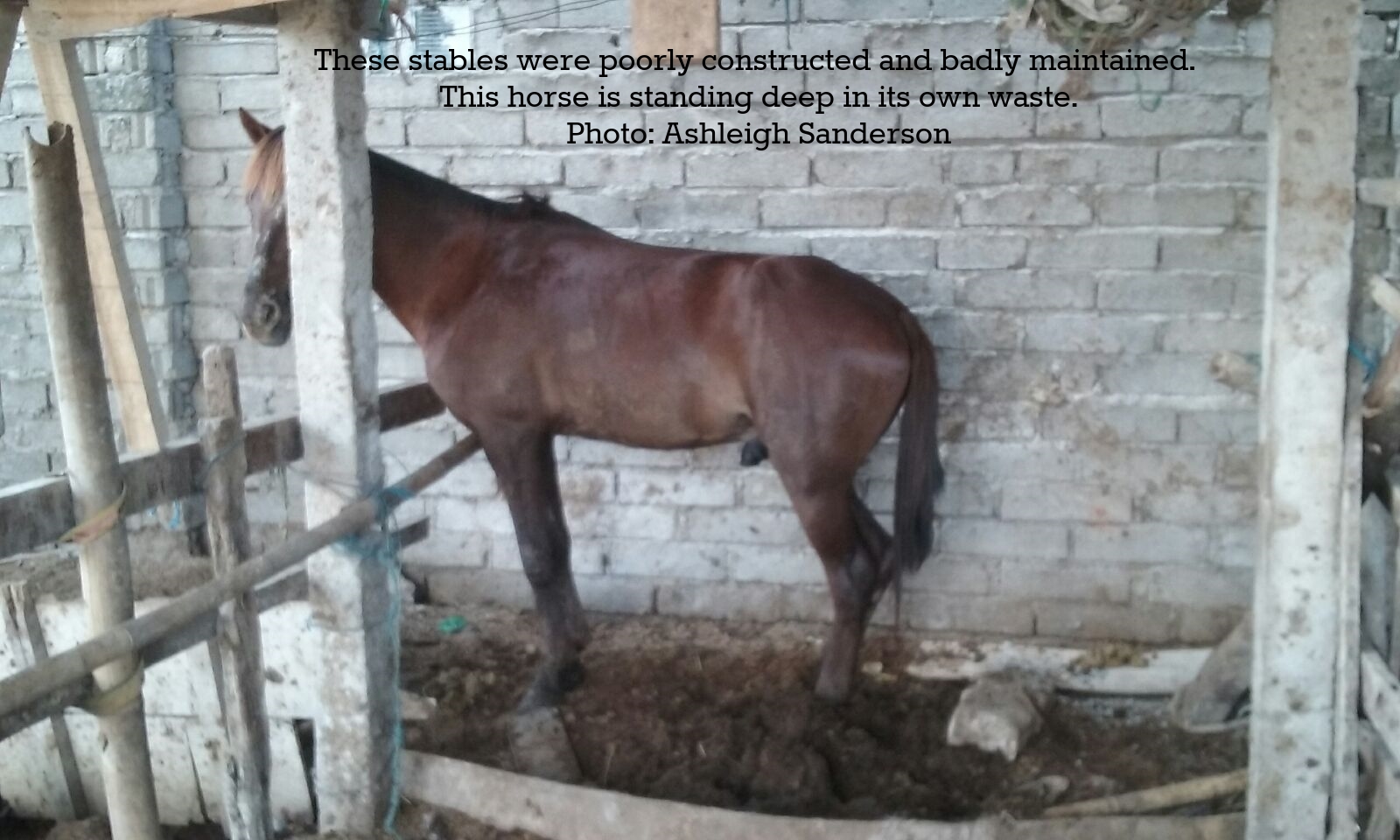

The island prohibits the use of motorised vehicles. All cargo – people, construction material and rubbish – are transported around the island by horse-cart. While the cidomo are a visible attraction of the island, the horse-carts used for other purposes do not always register on the tourists’ radars. And whilst the cidomo horses, also sometimes referred to as dongol horses, are usually standing still when business is slow, the “rubbish horses” – for want of a more refined term – are constantly on the move.

There are no rest days for any of the horses, but the rubbish horses seem to have pulled the short straw; they are worked for at least 12 hours a day hauling overloaded carts. Overloading is rife. Despite regulations that taxis should take no more than three people, including the driver, cidomo horses often strain under the heft of five fully-grown adults and luggage. And with new resorts and villas being fervently constructed every hundred metres or so, the rubbish horses run almost on tip-toe as bags of cement and wooden beams weigh their carts down into the dirt roads.

Gili T’s horses are of a breed indigenous to Indonesia. While not exactly ponies, they are smaller and shorter than the average Western horse. Robbe reckons that 20 tons of garbage are moved by these horses every day.

“And these horses, as you can see, are not all in great condition.”

We were in the stables where about 10 of the rubbish horses live. Their coats were dull, ribs too prominent and their eyes sad.

“Many people who happen to catch sight of these horses are horrified. And what they don’t realise is most of the horses on the island – there are about 250 - aren’t given fresh water to drink. They drink well water, which is salty and dirty, and they aren’t fed enough,” Robbe adds.

In addition to diet, faulty and incorrect equipment that look like home improvisations cause a fair bit of damage. Typical ailments include cysts and abscesses around the girth, sores on the neck and withers, infected eyes, cuts around the mouth that have been left to fester and poorly shod hooves.

It was around 2008 that Robbe initiated a free clinic for the island’s horses. She said, “It was difficult to convince them at first because the locals have their traditional way of doing things. They thought that giving their horses injections would make them sick or that feeding the animals dry hay would give them colic. Many still do think that!”

However, things have improved markedly since 2008. Robbe quipped, “At least now they drink desalinated water. It’s better than nothing.”

Serun from Lombok has worked on Gili T for about 12 years as a riding trail guide and farrier. I crouched next to him as he worked on a horse’s hoof. He pulled out the nails of a poorly fitted shoe and said, “You see? Too small.”

He added, “But the situation is better now. Before, the horses had sores everywhere.”